By Olamiju Fajemisin

Each time Nigerian-born cook, food writer, and cultural historian Ozoz Sokoh uncovers a new channel in the annals of Nigerian food and eating, she offers anecdotal morsels with it, too. The stories she tells make palatable the complex, tangential histories of the cultivation and preparation of indigenous and imported foods in pre- and postcolonial Nigeria, as well as in places suddenly populated by enslaved people of Nigerian origin and their descendants.

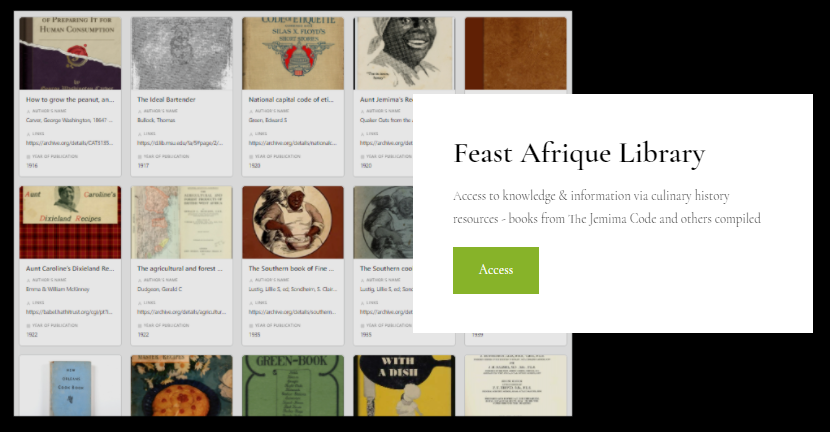

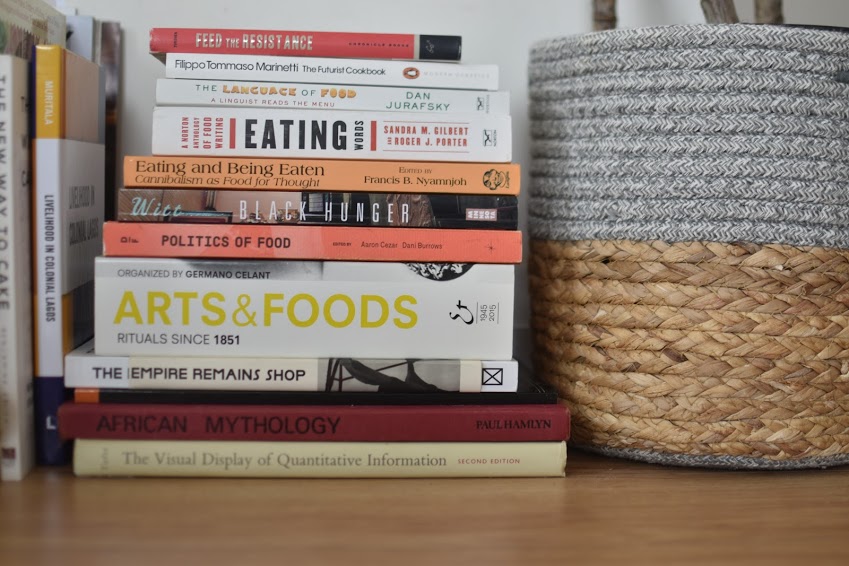

Sokoh’s tangents tend to cross the Atlantic—usually more than once, sometimes making a few stops along the way. Her rhizomatic practice of exhibition making, digital resource curation, teaching, and blogging, brings life to the notion of food as a key to a culture.

The pan-diasporic, auto-ethnographic scope of former geologist Sokoh’s research is informed as much by empirical research methods as it is by her long-had penchant for writing, and her newly learned museological skills. Sokoh’s installations and presentations invite us to speculate on undocumented histories with the help of empirical facts pertaining to Nigerian agriculture and cuisine, as well as etymological evidence found in old dictionaries.

Participating in the current edition of Forecast under the mentorship of Swiss-born Cameroonian curator, Koyo Kouoh, Sokoh is in the midst of developing a series of short documentary-style films, narrated by spoken-word artist Tolu Agbelusi. The patterns within Sokoh’s work are at times unpredictable—ricocheting centuries through time, across borders and language—and yet we can only marvel at them.

The nature of this project, Coast to Coast: From West Africa to the World, coincidentally pays heed to Kouoh’s description of her own practice as an “organic imposition,” that is, a practice in constant evolution, one which responds to different needs as they arise.