Reus and Du Yun’s time in Kumasi included workshops and meetings with local artists and musicians, such as Ibrahim Mahama and legendary highlife guitarist Koo Nimo. The two sat down for a conversation, and later, an interview with Va-Bene to talk about their experience there.

Du Yun: How has the work-stay influenced your work process, and the evolution of Celestial Fruit on Earthly Ground?

Jonathan: Forecast organized the work-stay to allow us to work closely and interactively on the development of this work. That alone has been an invaluable experience. For this work in particular, actually being in Ghana and learning from Du Yun’s experience by example is fundamental. But the work-stay is not only an extension of the mentorship, it has also become an essential part of the work itself.

It was quite a struggle to make our work-stay possible in Covid times. Originally I wanted to go to Suriname, because my project began with the Surinamese “creole bania,” the oldest banjo that still exists in the world, and I wanted to connect to stories and imaginations around this instrument. We were ready to go. I had built ties with fantastic collaborators there, such as the artist Marcel Pinas who runs the Kibii foundation in Moengo, and Marisa Piepelenbosch of the National School of Folk Music in Paramaribo. But unfortunately, Covid-related restrictions in Suriname prevented us from traveling there this time. Our second option was Ghana, because of the strong cultural connection between Akan traditions in Ghana and the traditions still practiced by Surinamese Maroon communities, who despite the conditions of slavery and ongoing pressure from colonial powers and Christian missionaries were able to preserve aspects of Akan traditions over centuries. So to contextualize the banjo (banya) in Suriname, it’s also important to know and experience the land and stories of Ghana.

Thanks to the social connections that I was able to develop through Forecast, I had already met Va-Bene, and was already thinking of ways to bring her into the project after learning about her associations of the banjo with the Ghanaian church, so it was natural to reach out to her when the idea to work in Ghana came up. Last July, during the Forecast work week, we were talking about my love for the banjo, and she said, “It reminds me of the church!” That blew my mind. It was so far from my perception of what the modern banjo is, let alone that of most people in the United States. How does a North American “hillbilly” folk instrument become part of a church service in Ghana? It turns out Va-Bene was once a Christian pastor. And when she was a child, there were these church bands that are still common in parts of Ghana, and that’s where she saw a banjo for the first time. This is why I especially wanted to collaborate with Va-Bene and connect to her story. It is a deeply personal one that can expand into a great artwork, but also points towards a much bigger, complex network of cultural dynamics that the pathways of music cling to.

The banjo returns to West Africa via Christian missionary activities after multiple centuries of transformation on another continent, becoming part of the global influence of jazz music, and then is taken up in a different form by Ghanaian Christianity: an endless chain of appropriations across cultures and histories. Her story connects the past to the present and addresses the sometimes surreal, cognitively dissonant cultural heritage we carry in the long shadow of colonialism. Moments like this trigger me to think about how much you can actually go back. In a lot of the discourse around colonialism—and especially when people talk about decolonizing things—there’s this feeling of lifting colonialism, as if it’s a blanket you could take off. But looking critically at the ways culture is transmitted between people and regions made me realize there is no blanket you can peel off; but that colonization fundamentally alters the cultural DNA of both colonizer and colonized; it’s the “colonial virus” as Va-Bene would say. You can’t go back, but you can see the pathways behind you and choose how you will now work to move forward. Ve-Bene’s experience, together with her own battles with religious colonialism in her artistic work, and being present with her in Kumasi, blessed me with a much more complex understanding of these issues. This kind of micro/macro dynamic where multiple time periods, traditions, and power structures exist simultaneously is part of how the micro-commissioning model fits into the broader scope of the work. I would feel like this work was successful if others are able to take away a similar alteration, or virus, in their thinking.

Du Yun: Often in my practices and engagement I think that the land itself, the country, and the people who live there—we cannot take them out of the work. Otherwise it would exist in a vacuum. So much so that everything has to do with the social context and the cultural heritage.

Va-Bene is also one of the most fantastic artists that I have encountered. Not only is she a powerful performance artist, she’s also a powerhouse in that she is the founder and artistic director of pIAR (Perforcraze international Artist Residency). It’s wonderful to see a space like this that’s not supported by the government but through the individual artists’ work and a shared engagement that a vision is created of what art can really shift in the social dynamic. I think there is also another layer of education here.

Jonathan: Absolutely! It’s been transformational for me to be at pIAR. For me, learning comes from seeing and doing. And I have always been hungry for role models. This work-stay has blessed me with two incredible new colleagues, Du Yun and Va-Bene, who both lead by example. Something Va-Bene does that I greatly admire is that she uses her status, the privilege of her education and the power of her knowledge, to mentor and educate other artists in her community, to empower them to understand other options and potentials for their art.

Being in Va-Bene’s presence, with the way she so proactively creates the world she wants to live in through education, was very resonant for me, because I’ve personally worked hard to try and self-educate myself out of the form-and-craft focus of my art education toward a more empowered practice. In the Netherlands I also co-organize an artist initiative and regularly organize community events and alternative educational initiatives. Working together has transformed the nature of my work in nearly all its forms. Also, seeing how Va-Bene leverages her own resources reminds me of how privileged we are in the Netherlands to have government funding that helps artists who do not have Va-Bene’s indomitable spirit to still produce work, and in many cases flourish.

Du Yun: [introduces Va-Bene] We were just talking about how instrumental you are to us! Not only because of the work-stay and the inspiring work you do at pIAR. You are also a collaborator for a micro-commission for Celestial Fruit. I’m interested to know to know about your interaction with Jonathan.

Ve-Bene: I always go back to that Zoom conversation! [laughs]. Forecast created an opportunity [in July 2020] and said “Hey, you can just look among the fellow artists and then we will link you to have outside conversations.” Forecast is doing something revolutionary; what they are doing is also an intervention. I chose three people and Jon was one of them and then we were just having a conversation. We never talked about something we want to do together; we were just thinking out loud. And then the banjo came up. And it just hit me as a kind of nightmare one day, and then again as a kind of an invasion and it took me back into the past. I don’t know how this happened to my imagination but I began to see this banjo as a very huge instrument. This is how the conversation started. I wasn’t expecting it, but later, Jon got back in touch and said, “We’re interested in having a work-stay in Ghana,” and I was like “Oh my goodness!” And today we’re sitting here together and talking about banjo as a performance.

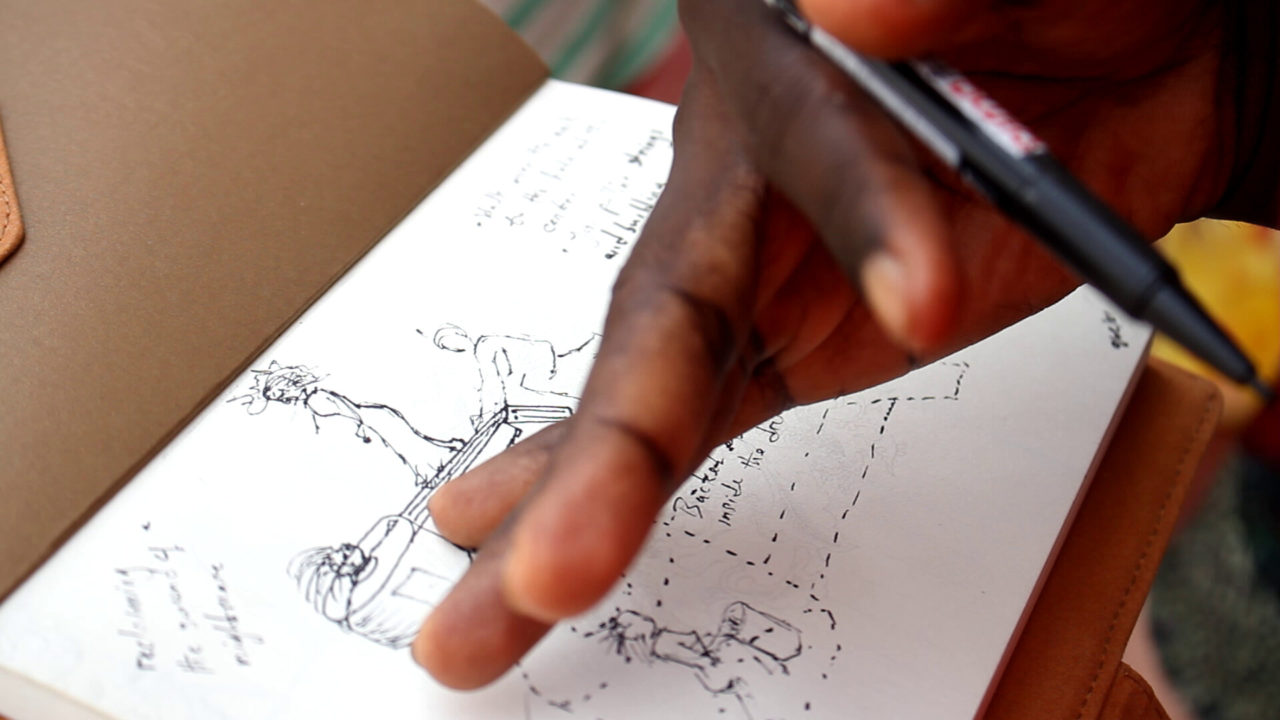

Jonathan: Va-Bene and I had a good conversation when I got here, and a few days later she had a sketchbook full of drawings. She had the idea to build a giant banjo, because in her mind she remembers being a child and seeing the banjo on the wall and feeling like it was this overwhelming presence. So she wanted to create something monumental that would have to be overcome.

Du Yun: Because I actually witnessed this beautiful relationship between you, and Jon told me about the communications you’ve had. And obviously I’m such a fan of your work. So I thought it’s such a great way to collaborate because I’m all about deep collaboration. You can always think that you can work together, but can we really shatter what we know, and look at each other’s performances and practices and truly question what have I been comfortable with? What’s my history and my lineage? Deep collaboration means thinking across regions, from the ground up. This is what I’m interested in witnessing and … I’m witnessing it here.