Text by Pablo Larios

Photos by Camille Blake

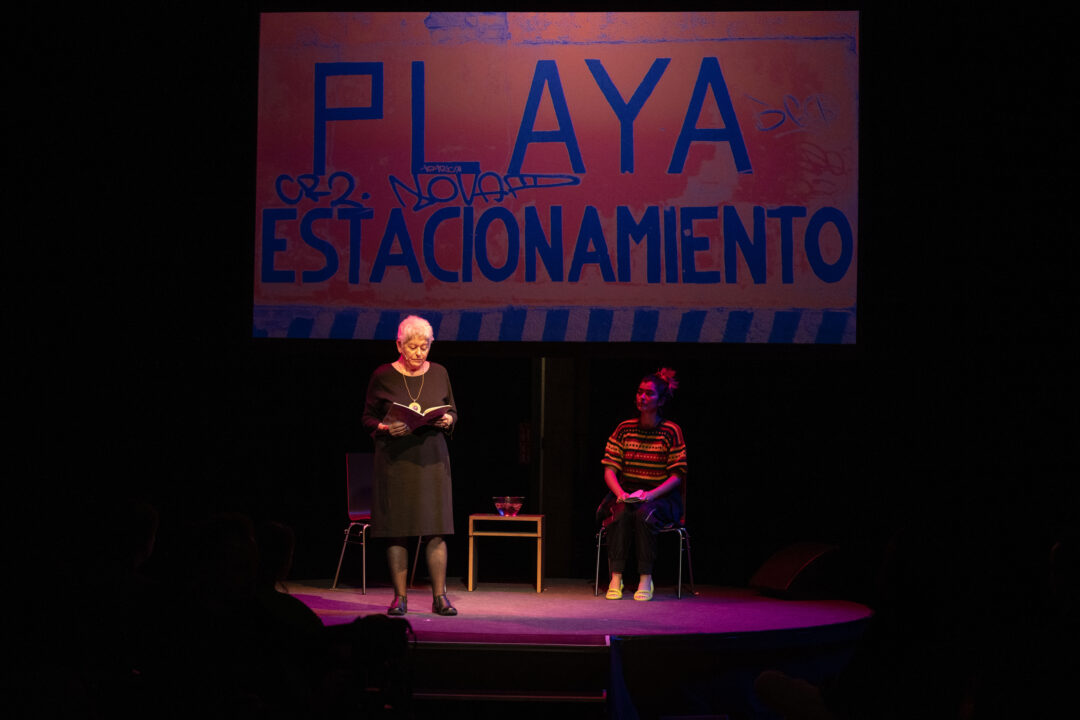

Some stories have no beginnings, or at least no beginnings commensurate with the real experiences of the people who share them. Marcela Huerta’s White Horses Always Run Home is one such story. Marcela is a poet and writer who, in their project for Forecast, confronts aspects of inherited grief, loss, and trauma as experienced by their own mother, the folk singer, performer, and artisan Yolanda Huerta. Marcela and Yolanda use poems, theater, games, and somatic activities to work through and reinscribe what Marcela calls Yolanda’s “geographies of trauma”: bottomless passages through a horrifying displacement that, perhaps, nobody but Yolanda can describe. But that’s just it. Who can ever re-inscribe the traumas of the displaced?

“This excess of words is a response to being silenced,” Marcela writes of their own roving and multivocal writing. White Horses Always Run Home navigates many universal experience—silencing, movement, labor, trauma—but it’s always about the transmissibility of particular experiences and our attempts and failures to describe and retell these acts. Which is to say, it’s also about poetry. It’s also about the specific relations that family lodge us within, and about how incommunicable these relations are, even as they are transferred within and externalized through the body: which is to say, this is a project of performance as a form of bodily reckoning.

Caballito Blanco

White Horses Always Run Home begins with Marcela’s attempt, about half a decade ago, to actively picture Yolanda’s life in Chile before her life as an exile. Marcela, who was born and grew up in Canada, was told stories by their mother about the Chilean coup. In contrast to the habituated silence that often exists among many survivors, Yolanda gave Marcela snippets of experiences, but these were (Marcela says) rather fragmentary and decontextualized. This sense of narrative fragmentation is an important starting point because it allows for the arrays of verbal, bodily, and visual bricolage that give life to White Horses Always Run Home.

In a chapter entitled “Going Home,” Marcela explains the origin of the project’s title—the lullaby “Caballito Blanco” their mother sang to them as a child (Little white horse, / Take me away. / Take me to the town, / Where I was born). In a startling prose sequence, Marcela describes a terrifying dream in which they imagined some of the violence their mother had experienced. After their mother soothed and calmed them in the wake of the nightmare by singing “Caballito Blanco,” Yolanda confessed to her daughter that she dreamt that she was dying at the same moment that Marcela was dreaming of their mother’s torture.

“This is a project about return. return of the scene of the crime. return to the terrain…,” Marcela writes in that chapter. The project is about tracing the “geographies of this trauma,” as Marcela says: virtually revisiting Maipú, Yolanda’s hometown; Santiago de Chile, where she was detained; Mendoza, where she was in hiding for a year; and Buenos Aires, where Yolanda and her sister left South America—and finally Winnipeg, where she landed in Canada and gave birth to Marcela.

Painful Legacies and Somatic Practices

Marcela writes about finding poetics in the body. A core part of their work concerns a type of physical theater, therapeutic movement, and visualization work known collectively as “somatic practices”—all focusing on the soma, the body as visualized by an inhabiting self. Proceeding from an insight that experience is inscribed on the body, present-day somatic practices use dance, theater, visualization, and games to undo trauma that, when further considered, manifests itself on a physical level. These practices of awareness then use the body to work through somatic trauma that remained buried.

Marcela’s practices refer, among others, to clown work developed by Canadian clown Richard Pochinko, while another touchpoint is derived from Yolanda’s experiences acting and writing for the play I Wasn’t Born Here (1988) by Lina de Guevara, which focused on the experiences of immigrant women from El Salvador, Chile, and Nicaragua. Some of the somatic connections among performance, writing, and healing can be read through Yolanda’s words, recounting realizations provoked around this time through yoga: “[d]oing this exercise I suddenly felt like fainting. Dizzy. I have this strange pain in my back, right down on the end point where there is a little bone. I remember, when I was in the stadium, a military man kicked my back there. He kicked me with his boot. It was a horrible feeling.”

Such a recollection can allow us to understand how unprepared Marcela felt, as they told me, for the actual challenges of confronting these experiences. In our conversation, they speak about their initial reluctance to even self-characterize as the child of a refugee and survivor—only to learn that many children of refugees often have the same sense of withholding from themselves. Already there, we can see how this repression persists through generations—even while such silencing afforded Marcela the ability to confront this legacy by turning to writing.

Communicating Without Communicating

From poems and zines to yoga and breathwork and a clown workshop, White Horses explores the many ways that suppressed histories can resurface through body awareness and body movements. Another important aspect of this project are the arpilleras made by Yolanda. This form of resistance art arose amid the Pinochet dictatorship, when thousands of people were abducted, made to disappear, or murdered. Chilean women, seeking and mourning missing relatives, turned to arpilleras as a form of vernacular art: naïve-seeming textile tapestries and quilts on potato sacks that contained messages expressing the horrors and suppression of the Pinochet regime. Predominantly crafted by women—often in workshops organized by the Roman Catholic Church, who also sold these to raise funds for women’s groups—these arpilleras were shipped or snuck out of Chile, containing pockets that enclosed secret messages. By the time the Pinochet regime outlawed arpilleras, they were an important form of political messaging and resistance. Marcela shows me an arpillera made by their mother, depicting Yolanda and her sister arriving in Winnipeg.

Marcela’s poem cenicientas begins with an experience of “learning how to write in English” while a child watches movies while a mother cleans houses. Other textual-bodily games include Palabritas, a round-robin poem and game in which two or more players construct a poem together following an initial prompt word (the poem starting with “Chile” finishes with the moving “BUT / SOON / THEY / WILL / BE / BUSY / WITH / THEIR / WORLDS / OF / SOLITUDE). Compartecuerpo (“share-body”) involves tracing the outline of a body on paper on the ground. The game’s participants are asked personal questions—but instead of answering the question verbally, the respondent simply points to a part of their body.

How do we talk about our families, and do we need to talk about them at all? As an immigrant myself, I bristle with the overdetermined language used by people to categorize my own experiences, legacies. And so, I understand part of Marcela’s argument in affixing these experiences to the body as a form of bringing them to their primary geography: the body itself. This endeavor seems to me to be an attempt at communicating sometimes without communicating, which allows people to undo the painful legacies forced upon them from above.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Vimeo. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information