Text: Qu Chang

Photos: Camille Blake

When Liu Mei sent me the previews of her works, I was enveloped by the dark winter next to a forest north of Vilnius, Lithuania. Every day at 4pm, the thick, viscous night devoured the etiolated woods outside. Impenetrable darkness rendered the deep forest into a flat, pitch-black surface that warped tightly around my studio window. This first radical northern winter experience showed me to what extent darkness can flatten the exterior world, pushing one’s consciousness back into the body and its unexpected depth. I was fearful of sinking into myself, of sensing that the inner space is perhaps an integral part of the darkness outside—a horrifying realization. A local friend later told me that the Baltic winters were normally accompanied by the illuminating element of snow, at least before the intensification of climate change. When white snow reflected the moonlight, even night forests were navigable.

At nightfall, young people began to walk out of their houses and onto the streets in Shanghai. They held blank sheets of white A4 papers high above their heads. The silence on the city’s streets was so loud that the police came to stop them. This, what later unfolded into the nationwide White Paper Movement, has ended the lockdown order. These sheets of paper are, in fact, portals. They transport us out of confinement and into utopian imaginations, towards another world. Maybe the only things we can see on these blank sheets are dreams.”

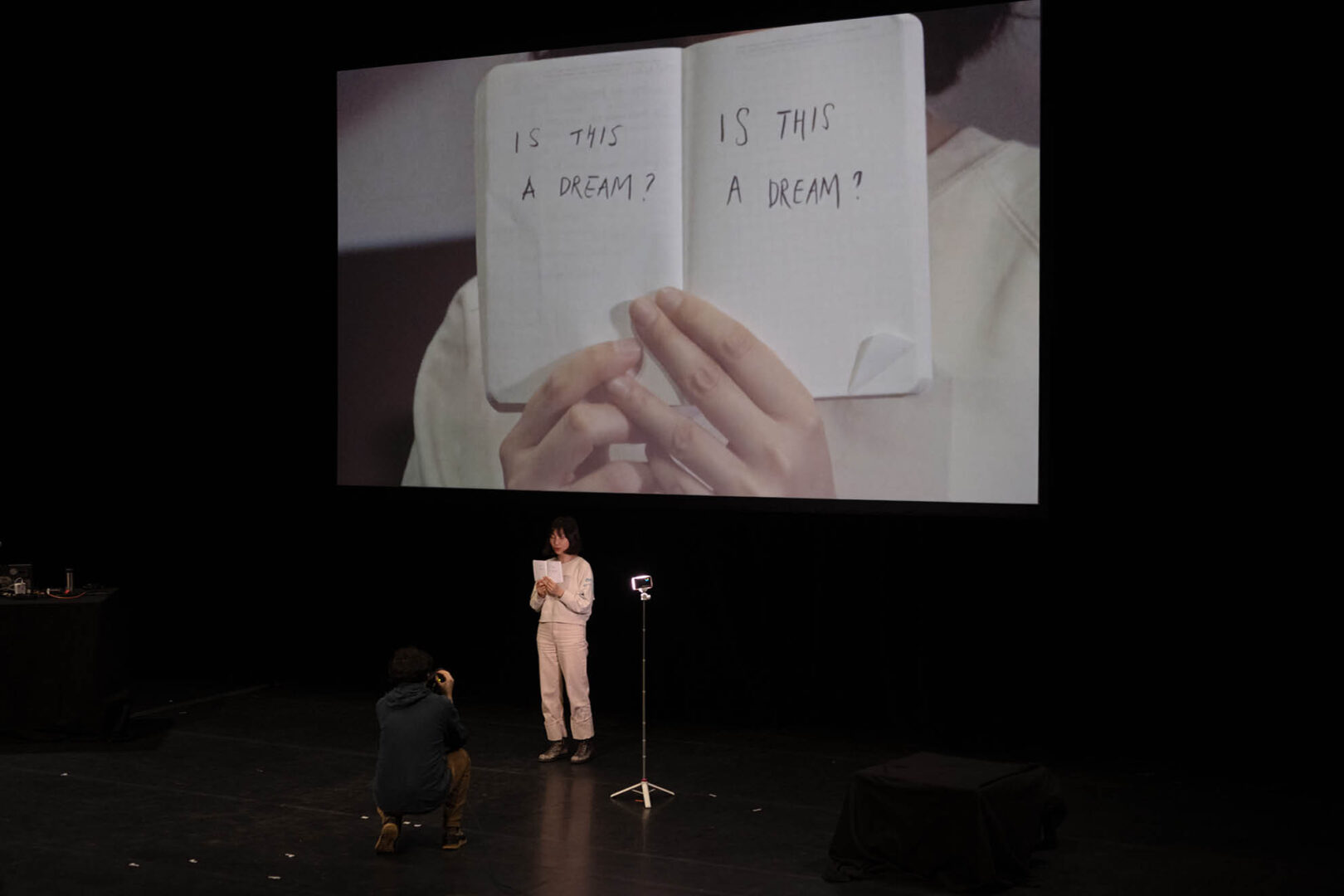

—Liu Mei, Lecture performance for Homesick for Another World, 2024

Mei’s artistic effort in her research-based series Homesick for Another World lies in her conscious exploration of depth in the often flattened narratives of dualism such as black and white, day and night, justice and evil. Oral accounts of different experiences of confinement, dreams, and sleep are her primary pathways to delve into the strata of darkness, sense the moving magma of hopes and despairs, and explore ways to situate oneself in a world of growing darkness.

Dreams as Portals

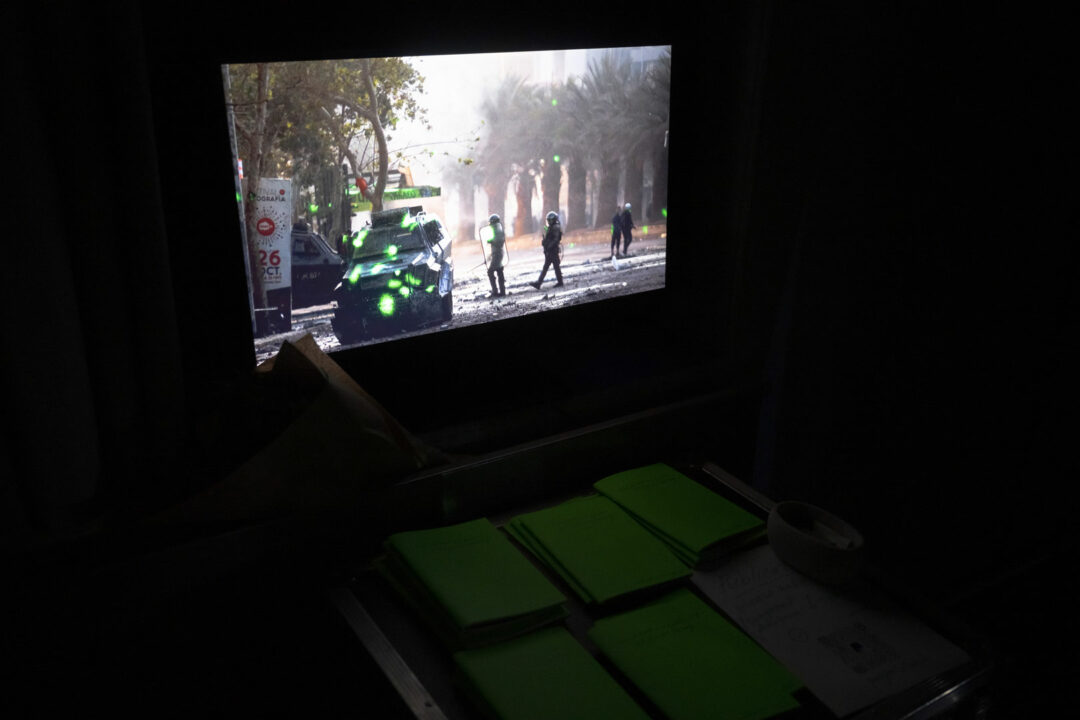

Starting from China’s state-enforced, nationwide lockdown during the COVID-19 epidemic, from which she escaped in early 2022, Mei’s research moves between various societies, times, and political struggles to map the underground rhizomes of connected structures of violence and spirituality. In a 2024 lecture performance of Homesick for Another World, she tells the story of a friend in China facing both immobility and starvation, who resorted to hibernation and slept eighteen hours a day.In extreme darkness, extended sleep opened spaces for them to confront stark reality. “Those days were fake,” her friend says. But they were also real. Dreams dissolve reality into fantasy, confinement into long, hallucinatory sleep. They reshape the physical condition and carry one through hardship. Dreams, in this sense, are not simply the spatial-temporal opposite of reality. At times, they are portals cutting through and transforming the real. Another protagonist in Mei’s work, the political dissident Lao Yang, imagined himself taking the sailboat printed on his bath towel on expeditions far and free during solitary confinement.

Dreams function in multiple layers in Mei’s exploration of socio-political darkness. They document personal memories and collective psyche amid proliferating conflicts and crises; they unfurl spaces for fabulation and fantastical thinking as alternative forms of remembrance against the backdrop of erased histories and unutterable feelings; they not only operate in parallel with reality but also permeate it, altering its perception while providing escape routes. During China’s lockdown, Grandpa Cui, who enjoyed relative stability with sufficient supplies at home, dreamt about his days of hard labor during the Cultural Revolution. More recently, Malaz, witnessing the dictatorship’s downfall in his homeland Syria, can also see the menacing shadow of new powers. Dreams can remind one to be vigilant and discerning on brighter days.

Shattered Subjectivity

The core realization in Mei’s exploration of the complexity of social darkness is the dismantling of subjectivity as an isolated entity. After all, before critically engaging in any political discussions and deconstructing entrenched systems of power, shouldn’t we first de-territorialize ourselves?At this point in my research, I am slowly sensing the presence of something bigger—an interconnected web of the universe of some sort. Maybe we have many doubles, in the past, in the present, in the future. One confined body, one outside; one suffering, one is fine. All the bodies are stacked on each other in a meticulously parallel universe. I wonder, in Northeast China, how many meters apart is Grandpa Cui’s dream body during hard labor from Lao Yang’s physical body in solitary confinement? […] Maybe our individuality is a lie. Maybe there is a bigger unity, a solidarity in very literal ways. Maybe we are physically connected through our dream bodies.”

—Liu Mei, Lecture performance for Homesick for Another World, 2024

In its current format, Homesick is a multimedia performance that envisions the multiplicities of bodies, consciousness, spiritual flows, and their co-existence through the connecting portals of dreams. Oral accounts, personal journals, and published texts are overlayed with polyphonic voices, performing bodies, and their ghostly extensions in projected lights. The work continuously articulates a conscious attention towards depth—be it the depth of political gloom, the body, or dreams. Fragments of glimmering shards scatter in the darkness. The task, contrary to modernity’s desire for scale, completeness, and piecing things together, is to unearth long-existing connections that require more than sight and logical thinking to perceive. It is precisely the not-yet-namable interrelations that reify the feeling of being homesick and the process of worlding in Mei’s artistic research.

The fluid nature of dreams is bound to usher in more uncertainty. Is the moving image, a medium created by modernity’s singular, authorial perspective, sufficient to imagine radical intersubjectivity? And more broadly, if bright is dark, past is future, you are me, is there any space for clarity and definitive actions? Perhaps what we should learn at this moment is to accept complexity and uncertainty as the constant condition for thinking and practicing, in contrast to illusory rationality. This might teach us to weave ourselves into more organic interactions with the world and invent more resilient acts of worldmaking. The thinking of dreams reminds me of the Taoist idea of wuwei, or inaction, which does not point to a simple nihilism or neoliberal laissez-faire policy, but to actions guided by an awareness of the myriad relations that connect one to the world. When darkness falls, we sleep and dream; when daylight casts in, we become watchful; when water starts flowing, we swim; when silence overwhelms, we sing.

Qu Chang is a curator and writer based in Berlin. She is the Curator of Discursive Practices at Haus der Kulturen der Welt and runs the exhibition programme between 2025 and 2026 at Shekmai Space with Echo Shi. Qu received her PhD in 2024 from the Cultural Studies Department at Lingnan University, Hong Kong. Previously, she served as a curator at Para Site, Hong Kong.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Vimeo. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information