Text by Sofi Naufal

Photos by Camille Blake

Journalist Alia Ibrahim tells me of an old Lebanese saying: “We mention it and hope it does not happen again.” Over time this expression has changed to “we mention it so that it does not happen again.” This semantic shift reflects a social movement taking place in Lebanon. The Lebanese are beginning to look to the past for answers. A generation of post-war journalists and artists are leading the way, extracting the suppressed truths of the country’s past in an attempt to heal old wounds and better understand the structures of Lebanon. French artist and researcher Alexis Guillier’s latest project has seen him join the archeological dig. From his home in Paris, Guillier spent much of 2022 trawling through archival documents on Lebanon. The research is for his upcoming film, a documentary that investigates a catastrophic accident on a film set in 1960s Beirut. Guillier is not Lebanese and before this project knew little of the country’s history. Now, under the mentorship of Ibrahim, he finds himself in the midst of an extensive research project uncovering the complex political, social, and economic webs that led not only to the accident but also the impoverished state of Lebanon today.

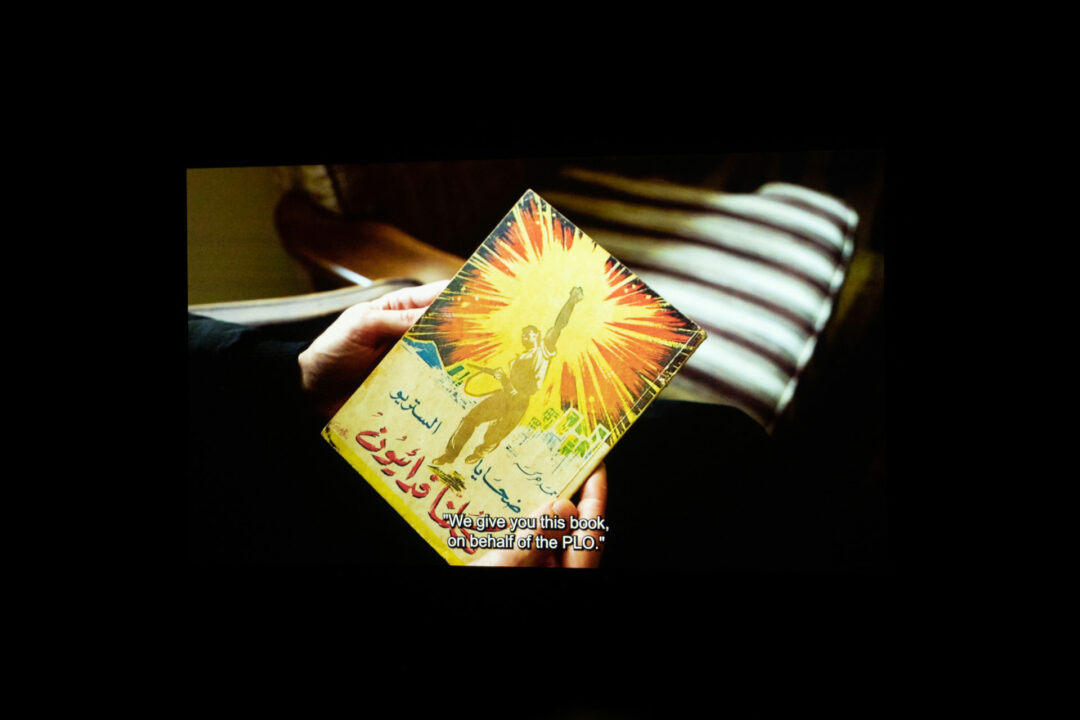

Beirut, 1968, director Gary Garabedian is filming the final scene of his pro-Palestinian film, Koullouna Fidayoun (We Are All Freedom Fighters), in a small basement club called Purgatoire. The scene shows a Fedayeen bomb attack on a Tel Aviv night club. Without enough funds for a generator, Garabedian harnesses extra voltage from the mains to power the smoke bombs that will imitate the bomb. Something goes wrong. A fire breaks out killing Garabedian and 19 other crew members. The 1968 catastrophe was one of the worst on-set tragedies in cinema to date but one that gained little traction. “What initially drew me to the project was that no one I knew had heard much about the accident,” Alia recalls. “I’m talking about journalists and people who were in the country at the time. People who would know.” We are left with two questions that Guillier’s documentary hopes to answer: How could a fire like this happen on a professional shoot and why was it so under-reported?

An accident on the controlled microcosm of a filmset punctures the protective membrane that surrounds it. Suddenly, the socio-political context of the work seeps in. The film enters a spontaneous dialogue with the realities of its environment. This is what attracts Guillier to exploring the history of cinema through its accidents. “Accidents will always reveal something about their context,” Guillier explains, “that’s why people in power hate to talk about them. They can destroy the system’s concrete narratives.”

Guillier’s previous work has largely focused on Hollywood and films such as Twilight Zone (1982) where an accident on set killed three of the cast. With Purgatoire (Cinema that Kills), Guillier delves into the more fragile social context of Lebanon for the first time. In 1968 many narratives in Lebanon were on shaky ground. Guillier’s research has led him to unearth a complex and interconnected matrix of failing systems: from the poor construction materials of the Purgatoire night club and Beirut’s unreliable electricity network, to the 1966 financial crash sparked by the bankruptcy of Palestinian-owned Intra bank, which also owned the film’s production house, Baalbeck Studios. Lebanon’s once-booming film industry was slowly crumbling, leaving Garabedian’s film severely underfunded. As Guillier’s research deepened, Lebanon’s lack of governance, money, and infrastructure reveals itself as the foundation for such a catastrophe. Lebanon was reaching the end of a prosperous era and the cracks in its foundations were beginning to show in the years running up to the 15-year-long Lebanese war of 1975.

Ibrahim is a passionate supporter of Guillier’s work. “The more I work with Alexis the more I think that there are no accidents. The connections are incredible.” In addition to her ability to read documents in Arabic, Ibrahim’s extensive knowledge of Lebanon’s socio-political climate is invaluable to Guillier’s project. Currently, she is investigating the immense powers afforded to the central bank governor in Lebanon. She locates these powers in the banking laws created around the time of the film’s accident in response to the collapse of Intra bank. “We started on these roots when we compromised clear governance and allowed a marriage between the political, private, and public spheres.” Guillier agrees, “Every aspect of this accident is not only a reflection of what was going on in Lebanon at the time but also what is happening now.”

In 2020, an explosion at the port of Beirut ripped through a city already ravaged by years of corruption, killing 228 people, and leaving hundreds of thousands homeless. The catastrophe was the result of gross negligence in the form of improperly stored ammonium nitrate. Today, Lebanon faces one of the biggest financial crises the world has seen. The political sphere is still a hotbed for corruption and the country’s infrastructure destroyed, its residents receiving barely an hour’s worth of state powered electricity per day. As with the port explosion, following the accident on Garabedian’s film set a number of conspiracy theories began to emerge. Ibrahim suggests that these types of events bring into question the very definition of an accident. They are perceived as attacks because in many ways they are.

Although it is generally agreed that the fire at Purgatoire night club was unplanned, it was the culmination of a long and persistent attack on the arts and the Lebanese people, an attack with negligence and greed at its heart. Conspiracy theories give people an answer in a climate where the justice system is failing them, but these theories also benefit those responsible. Ibrahim explains why: “This idea of conspiracy is very popular in Lebanon. Accidents start to become part of the collective entertainment and holding anyone accountable becomes impossible.” In 1969, a police investigation named two of the deceased, Garabedian and the director of production, as responsible for the accident. Lebanese director George Nasser disagreed with the verdict saying, “the catastrophe would have been the same with or without cinema.” Nasser expresses the exhausted mood of the country. Still today the victims of the Beirut Port explosion seek justice and compensation. The burying of information to protect the powerful is an entrenched part of Lebanon’s systems and is likely one of the reasons that the 1968 accident was so underreported.

Guillier’s work is an anecdote to this phenomenon. He explores what happens when, instead of moving past accidents, we investigate them. When we pause and, instead of diverting our gaze, look towards the painful parts of our histories. Accidents can be extremely traumatic but also revelatory. Guillier’s research lays the foundations for these powerful shocks to our systems becoming immense forces for change.